The Ferdinand Bolstraat is an interesting street in Amsterdam. Part of it is car-free now, another part is almost car-free. In the 1970s it was still considered a main arterial by some, but residents fought a fierce battle to get rid of the cars. At one time this involved burning car wrecks placed in the roadway upside down. Today’s scenes aren’t quite as brutal as that. Why don’t we have a look at what this street is like, and how that came about?

Whenever I travel in the Netherlands I always bring a camera to seize every opportunity to film for this blog, so that I can present you something every week. It was no different when I was on my way to Zaanstad, recently, for an evening presentation at the Annual General Meeting of the local chapter of the Fietsersbond (Cyclists’ Union). Since I had already made a video portrait of the Zaandam region I decided to briefly stop in nearby Amsterdam to film there.

The Ferdinand Bolstraat was reopened in January 2018 after it had been a building site for a very long time and that is why I decided to film the evening rush hour there. It is lovely to see all kinds of people using this street on foot and on their bicycles mixed with the occasional tram. Motor traffic is no longer allowed to use the north part of the street between the Stadhouderskade and the Albert Cuyp Market. Further south until the intersection with Ceintuurbaan the street is still one-way for motor traffic. I positioned myself at the corner of Quellijnstraat. This a street where my great-great-grandfather Jan Wagenbuur has lived in the mid-1890s. His grandson (and my grandfather) Louis Wagenbuur was even born in Albert Cuypstraat in 1906. That is why I feel a strong family connection to this part of Amsterdam.

The latest redesign of the street came after it had been a building site for no less than 15 years. In May 2003 the city closed the street and started the construction of the new metro line under the historic city centre and also under this street. It took until July 2018 before that North-South metro line was opened. The Ferdinand Bolstraat was also reopened in July 2018.

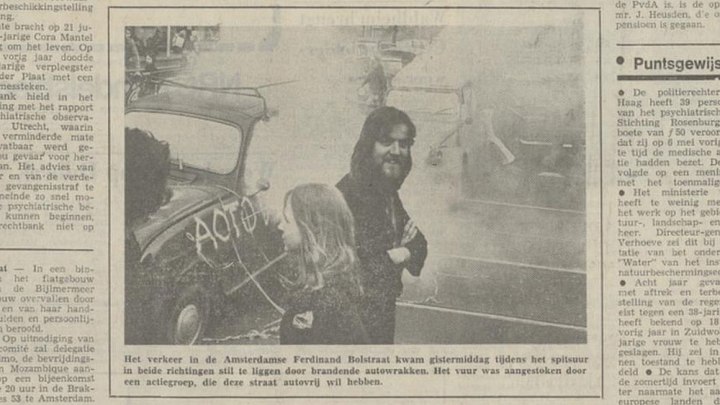

I hope some of the people who were protesting to get this street car free in the 1970s are still around to be proud. Some must be. For instance the people of the Stop de Kindermoord (Stop the Child Murder) organisation who walked into the main intersection with Ceintuurbaan hand in hand in December 1972. Exactly like mothers had done 19 years earlier in Philadelphia. For a moment it looked like they would get what they wanted when the city promised to close the street in 1973! But there was such strong opposition -from mainly shop keepers- that the city council changed its mind again, and again apparently when you read the 1970s papers. This yes-no-yes-no game by the Amsterdam council infuriated a lot of people. Another – far more radical – movement stepped in. With this “Actiegroep Ferdinand Bol Autovrij” (Action group Ferdinand Bol car-free) the protests intensified in a brutal way. At the height of what can only be described as riots it led to the burning car wrecks that were put in the street upside down several times in 1975. (I showed you a picture in an earlier post already.) It took over two more years before the street was finally closed to motor traffic. First, in January 1978, in both directions as a trial, which was changed after six months to only one direction because the shop owners were able to prove they suffered a 20% income loss. Later that one-way closing became the permanent solution (1979). It had taken a battle from 1972 to 1979 to get cars in one direction out! Time and time again opponents insisted in the newspapers: “nobody is happy with the redesign“. That particular article makes clear that the residents’ views didn’t count in the headlines. It is all about the shop keepers and their customers, who all lived outside the neighbourhood. In a side note you can read that the society of residents was very happy with the closing. You would think the street without most car traffic would be wider appreciated after a while, but even as late as 1995 one urban designer published a plan in which he “daydreamed about a redesign” of this area around the Albert Cuyp market. His daydream would open up Ferdinand Bolstraat again, for motor traffic in both directions. And not only there, some other streets in the area, which had also been closed to motor traffic, would see car traffic again in both directions. That plan could fortunately never come to life, because the construction of the metro line, from 2003, turned the whole neighbourhood into a huge building site.

It took 15 years, but once the tunnels for the metro were finally dug, and the underground station of “De Pijp” on this location was finished, the area above ground could be reconstructed. The city has made a plan for the entire route over the metro-line. From Central Station to the exhibition halls of RAI, a distance of 4 kilometres, the redesign of all the streets will offer much more space for walking and cycling. After the streets had been closed to motor traffic for all that time it would have been stupid to bring cars back and fortunately that wasn’t done. The reconstruction plan was named “Rode Loper” (Red Carpet) and that referred mostly to the colour of the brickwork that would form the street surfaces. A lot of that project has now been finished. Other parts (such as the Central Station island I wrote about earlier) are still under construction. The south part of Ferdinand Bolstraat will now be taken up. That part is and will stay accessible for car traffic but by getting rid of two parking lanes there is more than enough space to widen the cycle lanes and the footpaths for pedestrians. There too it will become very visible that the car is no longer king in the Netherlands, but what a battle it was! One that isn’t over yet either, as the international websites have noticed too, one by one the streets of Amsterdam become car-free (or almost car-free).

This week’s video: a look in car-free part of Ferdinand Bolstraat in Amsterdam

during the evening rush hour.

You make it sound as if the street was closed between 2003 and 2018, which it wasn’t the Nord-Zuid metro line was dug using boring machines, not cut-and-cover.

Was the tram always single-tracked at this spot or did they change the track layout during the redesign?

Used to be double tracked. They did it for a short section so they could create wider cycle and footpaths on this busy stretch. This is possible because there’s already a metro line underneath and the trams frequency therefore went down.

♥from #Ilpartitodellabicicletta

Wow, those “peace-loving hippies” in the 1970’s sure knew how to demand action. We need more of that today.

And below is just part of the resume of that “dreamer” who advocated to bring back automobile traffic to the hard-fought-for car-free street.

SHELL GAS AND POWER INTERNATIONAL BV

Managing Director–2005-2010

ROYAL DUTCH/SHELL

Secretary of various Group Committees (Sustainable Development, Brand and reputation, Social Investment) 2001-2003

amai…

Amsterdam children fighting cars in 1972 | BICYCLE DUTCH

Great post again. I remember when Ferdinand Bol was offered to pedestrians for Christmas in 2006. The construction works had just finished the building of the metro station roof and there was some time before the next works could start.

The small section between Centuurbaan and Albert Cuypstraat, were for month bikes and pedestrians where fighting over the narrow lines left to them, could finally breath.

http://meinamsterdam.nl/noel-sur-ferdinand-bolstraat

I also regret I see no mention of early 60’s projections to change the Pijp into a futuristic business district with high rise towers and flying cars.

Yet again, another great blog, and video to go along with it.

Well done, Marc